In 1900, 18 percent of all American workers were under the age of 16.

BY MADISON HORNE

For employers of the era, children were seen as appealing workers since they could be hired for jobs that required little skill for lower wages than an adult would command. Their smaller size also allowed them to do certain jobs adults couldn’t, and they were viewed as easy to manage.

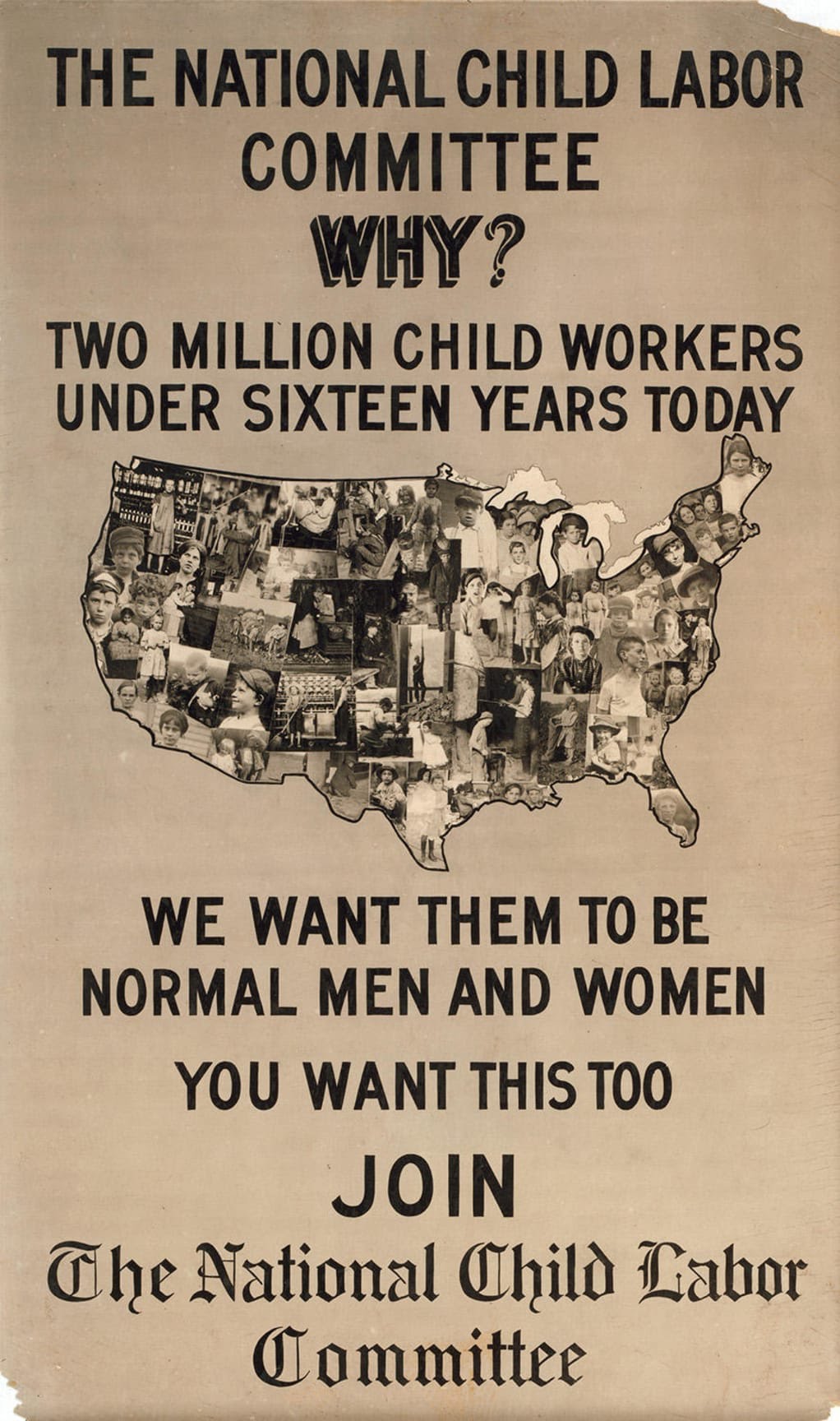

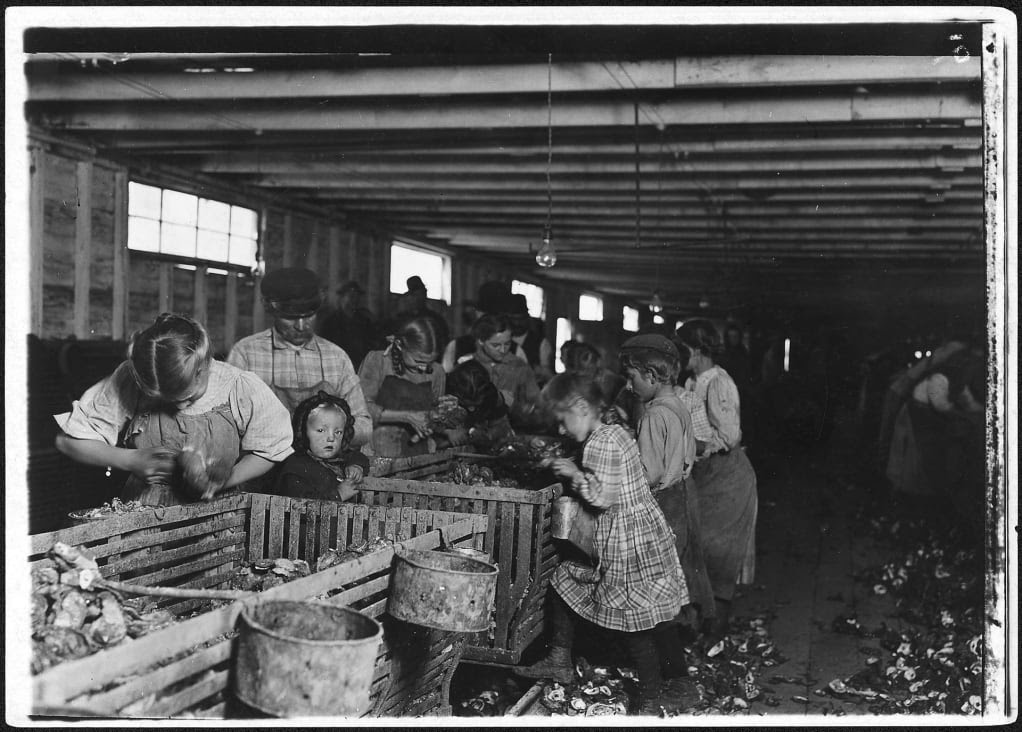

In 1904, the National Child Labor Committee formed in the hopes of ending the horrors of child labor. Teams of investigators were sent to collect evidence of the harsh conditions children were working in. One of these investigators was the photographer Lewis Hine, who traveled across the country meeting and photographing children working in a variety of industries.

Lewis Hine quit his job as a New York City school teacher to join the National Child Labor Committee. His goal was to open the public’s eyes to the exploitative nature of children’s employment, and to help ignite legislative change to end these abusive practices. Although the effects weren’t immediate, the appalling scenes he captured with his camera succeeded in drawing attention to the plight of children in the workforce.

8-year-old Jennie Camillo lived near Philadelphia and for the summer worked picking cranberries at Theodore Budd’s Bog in New Jersey, September 1910.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

These boys are all cutters in a canning company. August 1911.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

9-year-old Minnie Thomas showed off the average size of the sardine knife she works with. She earns $2 a day in the packing room, often working busy late nights. August 1911.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

This young worker, Hiram Pulk age 9, also worked in a canning company. He told Hine, “I ain’t very fast only about 5 boxes a day. They pay about 5 cents a box.” August 1911.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

Ralph, a young cutter in the canning factory, was photographed with a badly cut finger. Lewis Hine found many several children here that had cut fingers, and even the adults said they could not help cutting themselves on the job. Eastport, Maine, August 1911.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

Many children worked at mills. These boys here at the Bibb Mill in Macon, Georgia, were so small they had to climb the spinning frame just to mend the broken threads and put back the empty bobbins. January 1909.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

Young boys working in the coal mines were often referred to as Breaker Boys. This large group of children worked for the Ewen Breaker in Pittston, Pennsylvania, January 1911.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

Hine made a note about this family reading “Everybody works but… A common scene in the tenements. Father sits around.” The family informed him that with all the work they do together, they make $4 a week working until 9 p.m. each night. New York City, December 1911.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

These boys were seen at 9 at night, working in an Indiana Glass Works factory, August 1908.

Lewis Hine/The U.S. National Archives

7-year-old Tommie Nooman worked late nights in a clothing store on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington D.C. After 9 p.m., he would demonstrate the ideal necktie form. His father told Hine that he is the youngest demonstrator in America, and has been doing it for years from San Francisco to New York, staying at a place about a month at a time. April 1911.

Katie, age 13, and Angeline, age 11, hand-stitch Irish lace to make cuffs. Their income is about $1 a week while working some nights as late as 8 p.m. New York City, January 1912.

Many newsies stayed out late at night to try and sell their extras. The youngest boy in this group is 9 years-old. Washington, D.C. April 1912.